Demystifying the role of women in water diplomacy and promoting action for strengthening it, was the theme of an online Consultation Workshop that was held on 28 July 2020 (10:30-14:30 CET) and brought together more than 70 participants from the MENA region, the vast majority of them women. The workshop was a joint endeavour of GWP-Med and the Geneva Water Hub and was financially supported by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) in the framework of the “Making Water Cooperation happen in the Mediterranean” Project, aka Water Matchmaker Project.

During the 4-hour workshop, the stakeholders, representing government institutions, civil society organisations, private sector and academia, delved into the key findings of Women & Water Diplomacy in the Middle East and North Africa: A Comparative Study of Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco and Palestine.

The Comparative Study represents a milestone in the collaboration that the Global Water Partnership – Mediterranean (GWP-Med) launched with the Geneva Water Hub in spring 2020 on the role of women in water diplomacy. This technical/ mapping work looked into the current status and challenges facing women in water diplomacy/ transboundary water cooperation settings in the MENA region, capitalising on the methodology used for a similar mapping exercise undertaken in 2017-2018 in Jordan, Lebanon and Palestine. The current effort has reviewed and updated the work in the three countries and expanded the mapping to the Maghreb sub-region by including the cases of Egypt and Morocco. The Comparative Study has been prepared with the contribution of five leading female water and environment experts from the five countries and represents an independent line of work.

Further to discussing the key findings of the Study, the Workshop had among its objectives to collect specific input from the participants and speakers on the elements of a good water diplomat and the capacity building/training that can enforce this.

In this context, one of the Workshop sessions included lively exchanges on the elements of a good water diplomat. Through targeted interventions during high-level panels, prominent female and male figures in water diplomacy in the MENA region shared their experience in the field and offered insights on what makes for a good water diplomat.

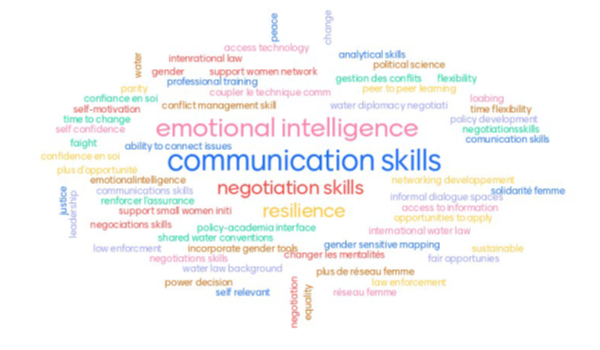

The Workshop concluded with a forward-looking session, during which the participants identified specific capacity building needs for making women change agents in water diplomacy and discussed options for making this happen. Βelow is a schematic representation of the interaction:

In terms of next steps, the co-authors will fully take into account and integrate in the Comparative Study the input and insights received during the Workshop. In this respect, the Study’s chapter on the elements and skills of a good water diplomat will be enriched with the suggestions of the panellists, while the chapter on the needs and training will build on the participants thoughts and include the mapping of existing mechanisms for skill development and collaborations and will also be enhanced with an action plan. The revised version of the Comparative Study will be prepared in late September and shared with the participants.

Importantly, by having at its core peer-to-peer exchanges and learning, the Workshop set the ground for the initiation of a community of practice of women in water diplomacy across the MENA region. The work on Women & Water Diplomacy in the MENA region is not a sole activity within a project, but aspires to become an initiative, grounding itself on the critical mass of the workshop participants who have been active contributors to the development of the Comparative Study. The enthusiasm of the participants reinforced the commitment of GWP-Med and the Geneva Water Hub to the initiative, with the Workshop signalling the beginning and the first step in the process.

Some excerpts from the Comparative Study

Why water diplomacy and why emphasise the role of women in water diplomacy?

In 2017, the Security Council held a briefing on Preventive Diplomacy and Transboundary Waters[1], emphasising the role of water diplomacy and cooperation in conflict prevention. This illustrates the growing awareness of the need to strengthen preventive diplomacy in all its dimensions and water is an integral part of this effort. ‘Water, peace and security are inextricably linked’, was the opening line of the UN Secretary General Mr. António Guterres in the said meeting.

The growing imbalance in global water supply and demand leads to tensions and conflicts and could potentially evolve into a widespread threat to international peace and security. It is indicative that for the 8th time in a row, water crises ranked as a top global risk in the 2020 World Economic Forum Report[2]. At the same time, water deprivation is increasingly seen as a fundamentally political and security problem, and not confined only within the realms of human development and environmental sustainability. After recognising water formally as a foreign policy issue in 2013[3], the EU Foreign Affairs Council adopted the new conclusions on EU Water Diplomacy[4] making the case for linking water, security and peace, including the potential of water as an instrument for peace.

For water diplomacy to bear fruits, the inclusive participation of all stakeholders in the process is an absolute must; including women. However, the role of women in water diplomacy related decision-making has been underestimated, despite the acknowledged essential role of women in peacebuilding, conflict management and sustaining security, as reaffirmed by the landmark United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security (adopted on 31st October 2000[5]) and by the eight resolutions on the issue adopted thereafter[6]. Further emphasis on encouraging and capacitating women to take up such positions has strong merits that are yet to be explored.

The presence of women in decision-making positions in the water sector is not an end in itself and transcends the simplistic approach of securing quotas and sharing seats; it is about the need for a balanced representation of women and men in related processes at all levels and weighing their influence in shaping priorities, in pursuing common objectives and in reaching decision. It is part of a comprehensive approach towards water security that effectively addresses diversity, inclusion, social equality, and women’s role in the integrated and sustainable management of water resources[7].

Evidence shows that gender equality is critical to achieving the totality of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)[8] and the Paris Agreement[9], however, related research usually focuses on how policies affect women as if they are only passive victims[10]. As obvious, this misses the big picture where women are also driving change.

The situation in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region is no different, where gender inequality concerns have traditionally taken a back seat to the “larger” or “more urgent” issues of civil wars, foreign interventions, unemployment, corruption, and authoritarianism[11]. When it comes to the issue of the area of water diplomacy, the situation is even more dire; dedicated analyses concerning Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco and Palestine are provided in the following chapters of the Comparative Study.

Copyrights with:

[1] https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_pv_7959.pdf

[4] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2018/11/19/water-diplomacy-council-adopts-conclusions/

http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-13991-2018-INIT/en/pdf

[6] https://www.unwomen.org/-/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/library/publications/2017/wps-resolutions-poster-en.pdf?la=en&vs=4004

[7] https://www.gwp.org/globalassets/global/about-gwp/publications/gender/gender-action-piece.pdf The GWP Gender Action Piece includes four action areas with tangible recommendations on how to drive gender equality and inclusion in water resources management.

[8] https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwion5yp7ezqAhWL-6QKHSr1Ag8QFjALegQIAxAB&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.undp.org%2Fcontent%2Fdam%2Fundp%2Flibrary%2Fgender%2FGender_equality_as_an_accelerator_for_achieving_the_SDGs.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1VbdhIhnDBzyghl_342un6 and https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-and-the-sdgs